Almost anybody who has ever thought deeply about the universe sooner or later wonders if there is more than one of them. Whether a multiplicity of universes — known as a multiverse — actually exists has been a contentious issue since ancient times. Greek philosophers who believed in atoms, such as Democritus, proposed the existence of an infinite number of universes. But Aristotle disagreed, insisting that there could be only one.

Today a similar debate rages over whether multiple universes exist. In recent decades, advances in cosmology have implied (but not proved) the existence of a multiverse. In particular, a theory called inflation suggests that in the instant after the Big Bang, space inflated rapidly for a brief time and then expanded more slowly, creating the vast bubble of space in which the Earth, sun, Milky Way galaxy and billions of other galaxies reside today. If this inflationary cosmology theory is correct, similar big bangs occurred many times, creating numerous other bubbles of space like our universe.

Properties such as the mass of basic particles and the strength of fundamental forces may differ from bubble to bubble. In that case, the popular goal pursued by many physicists of finding a single theory that prescribes all of nature’s properties may be in vain. Instead, a multiverse may offer various locales, some more hospitable to life than others. Our universe must be a bubble with the right combination of features to create an environment suitable for life, a requirement known as the anthropic principle.

But many scientists object to the idea of the multiverse and the anthropic reasoning it enables. Some even contend that studying the multiverse doesn’t count as science. One physicist who affirms that the multiverse is a proper subject for scientific investigation is John Donoghue of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

As Donoghue points out in the 2016 Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, the Standard Model of Particle Physics — the theory describing the behavior of all of nature’s basic particles and forces — does not specify all of the universe’s properties. Many important features of nature, such as the masses of the particles and strengths of the forces, cannot be calculated from the theory’s equations. Instead they must be measured. It’s possible that in other bubbles, or even in distant realms within our bubble but beyond the reach of our telescopes, those properties might be different.

Maybe some future theory will show why nature is the way it is, Donoghue says, but maybe reality does encompass multiple possibilities. The true theory describing nature might permit many stable “ground states,” corresponding to the different cosmic bubbles or distant realms of space with different physical features. A multiverse of realms with different ground states would support the view that the universe’s habitability can be explained by the anthropic principle — we live in the realm where conditions are suitable — and not by a single theory that specifies the same properties everywhere.

Knowable Magazine quizzed Donoghue about the meaning of the multiverse, the issues surrounding anthropic reasoning and the argument that the idea of a multiverse is not scientific. His answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Can you explain just what you mean by multiverse?

For me, at least, the multiverse is the idea that physically out there, beyond where we can see, there are portions of the universe that have different properties than we see locally. We know the universe is bigger than we can see. We don’t know how much bigger. So the question is, is it the same everywhere as you go out or is it different?

If there is a multiverse, is the key point not just the existence of different realms, but that they differ in their properties in important ways?

If it’s just the same all the way out, then the multiverse is not relevant. The standard expectation is that aside from random details — like here’s a galaxy, there’s a galaxy, here’s empty space — that it’s more or less uniform everywhere in the greater universe. And that would happen if you have a theory like the Standard Model where there’s basically just one possible way that the model looks. It looks the same everywhere. It couldn’t be different.

Isn’t that what most physicists would hope for?

Probably literally everyone’s hope is that we would someday find a theory and all of a sudden everything would become clear — there would be one unique possibility, it would be tied up, there would be no choice but this was the theory. Everyone would love that.

But the Standard Model does not actually specify all the numbers describing the properties of nature, right?

The structure of the Standard Model is fixed by a symmetry principle. That’s the beautiful part. But within that structure there’s freedom to choose various quantities like the masses of the particles and the charges, and these are the parameters of the theory. These are numbers that are not predicted by the theory. We’ve gone out and we’ve measured them. We would like eventually that those are predicted by some other theory. But that’s the question, whether they are predicted or whether they are in some sense random choices in a multiverse.

The example I use in the paper is the distance from the Earth to the sun. If you were studying the solar system, you’d see various regularities and a symmetry, a spherically symmetrical force. The fact that the force goes like 1 over the radius squared is a consequence of the underlying theory. So you might say, well, I want to predict the radius of the Earth. And Kepler tried to do this and came up with a very nice geometric construction, which almost worked. But now we know that this is not something fundamental — it’s an accident of the history. The same laws that give our solar system with one Earth-to-sun distance will somewhere else give a different solar system with a different distance for the planets. They’re not predictable. So the physics question for us then is, are the parameters like the mass of the electron something that’s fundamentally predictable from some more fundamental theory, or is it the accident of history in our patch of the universe?

How does the possibility of a multiverse affect how we interpret the numbers in the Standard Model?

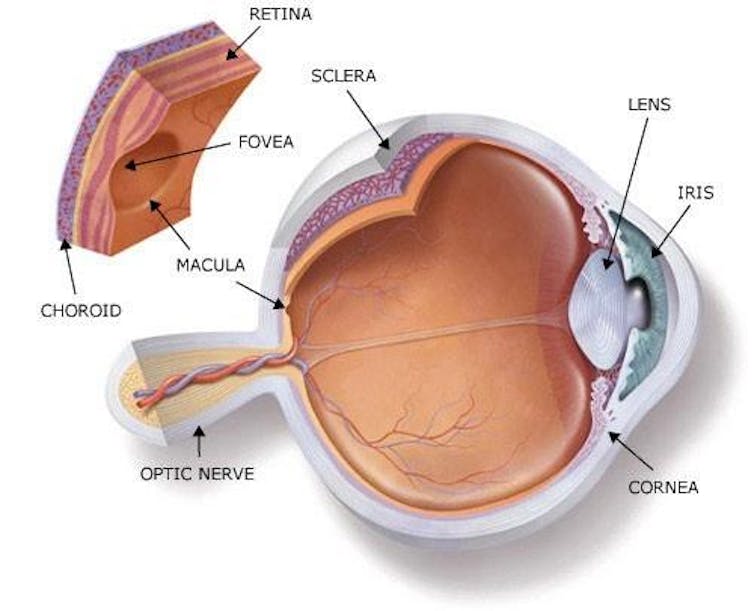

We’ve come to understand how the Standard Model produces the world. So then you could actually ask the scientific question: What if the numbers in the Standard Model were slightly different? Like the mass of the electron or the charge on the electron. One of the surprises is, if you make very modest changes in these parameters, then the world changes dramatically. Why does the electron have the mass it does? We don’t know. If you make it three times bigger, then all the atoms disappear, so the world is a very, very different place. The electrons get captured onto protons and the protons turn into neutrons, and so you end up with a very strange universe that’s very different from ours. You would not have any chance of having life in such a universe.

Are there other changes in the Standard Model numbers that would have such dramatic effects?

My own contribution here is about the Higgs field [the field that is responsible for the Higgs boson]. It has a much smaller value than its expected range within the Standard Model. But if you change it by a bit, then atoms don’t form and nuclei don’t form — again, the world changes dramatically. My collaborators and I were the ones that pointed that out.

There’s some maybe six or seven of these constraints — parameters of the Standard Model that have to be just so in order to satisfy the need for atoms, the need for stars, planets, et cetera. So about six combinations of the parameters are constrained anthropically.

By “anthropically,” you mean that these parameters are constrained to narrow values in order to have a universe where life can exist. That is an old idea known as the anthropic principle, which has historically been unpopular with many physicists.

Yes, I think almost anybody would prefer to have a well-developed theory that doesn’t have to invoke any anthropic reasoning. But nevertheless it’s possible that these types of theories occur. To not consider them would also be unscientific. So you’re forced into looking at them because we have examples where it would occur.

Historically there’s a lot of resistance to anthropic reasoning, because at least the popular explanations of it seem to get causality backwards. It was sort of saying that we [our existence] determine the parameters of the universe, and that didn’t feel right. The modern version of it, with the multiverse, is more physical in the sense that if you do have these differing domains with different parameters, we would only find ourselves in one that allows atoms and nuclei. So the causality is right. The parameters are such that we can be here. The modern view is more physical.

If there is a multiverse, then doesn’t that change some of the goals of physics, such as the search for a unified theory of everything, and require some sort of anthropic reasoning?

What we can know may depend on things that may end up being out of our reach to explore. The idea that we should be searching for a unified theory that explains all of nature may in fact be the wrong motivation. It’s certainly true that multiverse theories raise the possibility that we will never be able to answer these questions. And that’s disturbing.

Does that mean the multiverse changes some of the questions that physicists should be asking?

We certainly still should be trying to answer “how” questions about how does the W boson decay or the Higgs boson, how does it decay, to try to get our best description of nature. And we have to realize we may not be able to get the ultimate theory because we may not be able to probe enough of the universe to answer certain questions. That’s a discouraging feature. I have to admit when I first heard of anthropic reasoning in physics my stomach sank. It kills some of the things that you’d like to do.

Don’t some people even argue that though a multiverse would seem to justify anthropic reasoning, that approach should still be regarded as not scientific?

It’s one of the things that bothers me about the discussion. Just because you feel bad about the multiverse, and just because some aspects of it are beyond reach for testing, doesn’t mean that it’s wrong. So if it’s worth considering, and looking within the class of multiverse theories to see what it is that we could know, how does it change our motivations? How does it change the questions that we ask? And to say that the multiverse is not science is itself not science. You’re not allowing a particular physical type of theory, a possible physical theory, that you’re throwing out on nonscientific grounds. But it does raise long-term issues about how much we could understand about the ultimate theory when we can just look locally. It’s science, it’s sometimes a frustrating bit of science, but we have to see what ideas become fruitful and what happens.

An important part of investigating the multiverse is finding a theory that includes multiple “ground states.” What does that mean?

The ground state is the state that you get when you take all the energy out of a system. Normally if you take away all the particles, that’s your ground state — all the background fields, the things that permeate space. The ground state is described by the Standard Model. Its ground state tells you exactly what particles will look like when you put them back in; they will have certain masses and certain charges.

You could imagine that there are theories which have more than one ground state, and if you put particles in this state they look one way and if you put particles in another state they look another way — they might have different masses. The multiverse corresponds to the hypothesis that there are very many ground states, lots and lots of them, and in the bigger universe they are realized in different parts of the universe.

Even if a theory of particles and forces can accommodate multiple ground states, don’t you need a method of creating those ground states?

Two features have to happen. You have to have the possibility of multiple ground states, and then you have to have a mechanism to produce them. In our present theories, producing them is easier, because inflationary cosmology has the ability to do this. Finding theories that have enough ground states is a more difficult requirement. But that’s a science question. Is there one, is there two, is there a lot?

Superstring theory encompasses multiple ground states, described as the “string landscape.” Is that an example of the kind of theory that might imply a multiverse?

The string landscape is one of the ways we know that this [multiple ground states] is a physical possibility. You can start counting the number of states in string theory, and you get a very enormous number, 10 to the 500. So we have at least one theory that has this property of having a very large number of ground states. And there could be more. People have tried cooking up other theories that have that possibility also. So it is a physical possibility.

Don’t critics say that neither string theory nor inflationary cosmology has been definitely established?

That’s true of all theories beyond the Standard Model. None of them are established yet. So we can’t really say with any confidence that there is a multiverse. It’s a physical possibility. It may be wrong. But it still may be right.