Persuading Southern autoworkers to join a union remains one of the U.S. labor movement’s most enduring challenges, despite persistent efforts by the United Auto Workers union to organize this workforce.

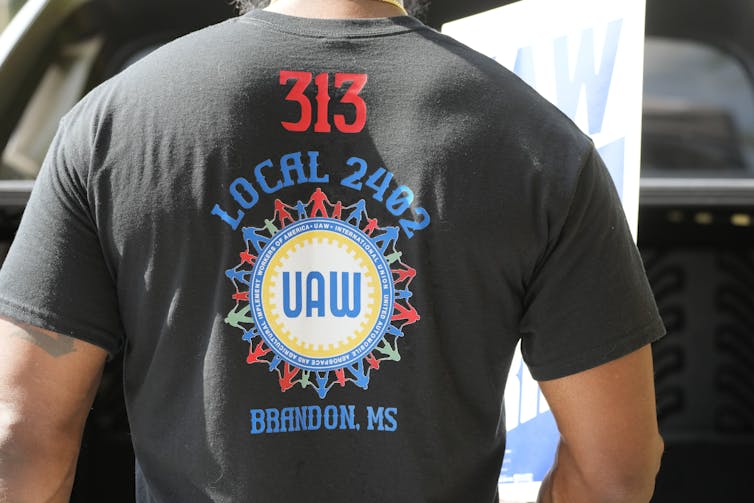

To be sure, the UAW does have members employed by Ford and General Motors at facilities in Kentucky, Texas, Missouri and Mississippi.

However, the UAW has tried and largely failed to organize workers at foreign-owned companies, including Volkswagen and Nissan in Southern states, where about 30% of all U.S. automotive jobs are located.

But after the UAW pulled off its most successful strike in a generation against Detroit’s Big Three automakers, through which it won higher pay and better benefits for its members in 2023, the union is trying again to win over Southern autoworkers.

The UAW has pledged to spend US$40 million through 2026 to expand its ranks to include more auto and electric battery workers, including many employed in the South, where the industry is quickly gaining ground.

Based on my five decades of experience as a union organizer and labor historian, I anticipate that, recent momentum aside, the UAW will face stiff resistance from Toyota, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and the other big foreign automakers that operate in the South. The pushback is also coming from Southern politicians, many of whom have expressed concern that UAW success would undermine the region’s carefully crafted approach to economic development.

Lauding the ‘perfect three-legged stool’

After the region’s formerly robust textile industry imploded in the 1980s and 1990s because of an influx of cheap imports, Southern business and political leaders revived the region’s manufacturing base by successfully recruiting foreign automakers.

The strategy of those leaders reflects what the Business Council of Alabama has described as the “perfect three-legged stool for economic development.” It consists of “an eager and trainable workforce with a work ethic unparalleled anywhere in the nation,” accompanied by a “low-cost and business-friendly economic climate, and the lack of labor union activity and participation.”

The prospect of a low-wage and reliable workforce has lured the likes of Nissan, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Kia, Honda, Volkswagen and Hyundai to the South in recent decades.

Although many of those companies negotiate constructively with unions on their home turf, the lack of union membership and the protections that go with it have proved a draw for them in the United States.

As journalist Harold Meyerson has noted, these foreign automakers embraced the opportunity to “slum” in America and “do things they would never think of doing at home.”

The absence of union representation is a major reason why.

Less than 5% of workers in six Southern states are union members, and only Alabama and Mississippi approach union membership levels above 7%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That’s below the national average, which slid to 10% in 2023.

Blaming unions for bad job prospects

One way automotive employers in the South have blocked unions is by portraying them as outdated institutions whose bloated contracts and rigid work rules destroy jobs by making domestic auto companies uncompetitive.

Automotive leaders in the South argue the region has developed an alternative labor relations model that provides management with flexibility, offers wages and benefits superior to what local workers have earned previously and frees employees from any subordination to union directives.

Southern automakers also draw on another powerful resource in resisting the UAW: public intervention by top elected officials.

In 2014, when the UAW attempted to organize a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga. Bob Corker, Tennessee’s junior U.S. senator and a former mayor of Chattanooga, weighed in as voting commenced.

Corker claimed he had received a pledge from Volkswagen’s management to expand production in Chattanooga if workers voted against the union.

Three years later, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant similarly urged Nissan workers to reject the UAW.

“If you want to take away your job, if you want to end manufacturing as we know it in Mississippi, just start expanding unions,” Bryant said in 2017.

A majority of the autoworkers heeded their conservative leaders’ advice in both cases and voted against joining the UAW.

Making dire warnings

With the UAW ramping up its organizing efforts again, Southern governors are sounding alarms once more.

“The Alabama model for economic success is under attack,” warned Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey.

She then asked workers: “Do you want continued opportunity and success the Alabama way? Or do you want out-of-state special interests telling Alabama how to do business?”

Unions “have crippled and distorted the progress and prosperity of industries and cities in other states,” South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster declared in his Jan. 24, 2024, State of the State address. He then issued an ominous call: “We will fight” the UAW’s labor organizers “all the way to the gates of hell. And we will win.”

The UAW counters that union membership means workers will get predictable raises, better benefits and improved workplace policies.

Changing context

Although these arguments from anti-union politicians haven’t changed much over the years, the context certainly has.

The UAW’s big wins on pay and benefits resulting from its 2023 strike against General Motors, Ford and Stellantis have increased its clout and credibility.

Many automakers with a U.S. workforce not covered by the UAW – including Volkswagen, Honda, Hyundai and other foreign transplants – responded by raising pay at their Southern plants. The union justifiably describes those raises as a “UAW bump.”

The UAW will presumably cite these pay hikes in its outreach to workers at Tesla and other nonunion companies involved in electric vehicle and battery production in which the industry is investing heavily.

“Nonunion autoworkers are being left behind,” the UAW’s recruiting website warns. “Are you ready to stand up and win your fair share?”

The pitch continues: “It’s time for nonunion autoworkers to join the UAW and win economic justice at Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Tesla, Nissan, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Subaru, Volkswagen, Mazda, Rivian, Lucid, Volvo and beyond.”

Some Southern autoworkers, meanwhile, have been expressing concerns over scheduling, safety, two-tier wage systems and workloads that they believe a union could help resolve.

It’s also clear they’ve been emboldened by the gains they have seen UAW members make.

Revving up

The UAW’s campaign is just starting to rev up.

In accordance with its “30-50-70” strategy, the union is announcing the share of workers who have signed union cards in stages. Once it hits 30% at a factory, the UAW will announce publicly that an organizing campaign is underway. At the 50% mark, it will hold a public rally for workers that includes their neighbors and families, as well as UAW President Shawn Fain.

Once it gains support from 70% of a plant’s workers, the UAW says it will seek voluntary recognition by management.

A recent National Labor Relations Board ruling provides unions with additional leverage in this process. If management refuses to recognize the union’s request, the employer would then be required to seek an NLRB representation election.

To win, unions need a majority of those voting. Under the new rule, if management is found to have interfered with workers’ rights during the election process, it could then be required to bargain with the union.

So far, the UAW has announced that it has obtained the support of more than half the workers at factories belonging to two of the 13 nonunion automakers it’s targeting: a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and a Mercedes-Benz factory near Tuscaloosa, Alabama. It has also obtained 30% support at a Hyundai plant in Alabama and a Toyota engine factory in Missouri.

I believe that the stakes are high for all workers, not just those in the auto industry.

As D. Taylor, the president of Unite Here, a union that represents workers in a wide range of occupations, recently observed: “If you change the South, you change America.”

Bob Bussel, Professor Emeritus of History and Labor Education, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.