A phone fixation may seem at odds with an attraction to books. But the latter may offer a much-needed reprieve from the former.

In our recent study of American Gen Z and millennials, we discovered that 92% of them check social media daily; 25% of them check multiple times per hour.

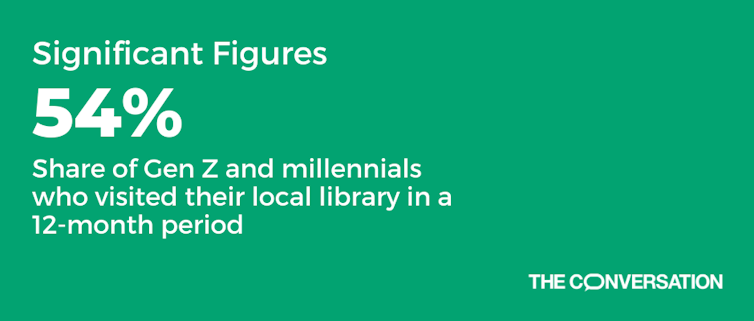

Yet in that same nationally representative study, we also found that Gen Z and millennials are still visiting libraries at a healthy clip, with 54% of Gen Zers and millennials trekking to their local library in 2022.

Our findings reinforce 2017 data from the Pew Research Center, which showed that 53% of millennials had gone to their local library over the previous 12 months. By comparison, that same study found that 45% of Gen Xers and 43% of baby boomers visited public libraries.

So why might Gen Z and millennials – sometimes characterized as attention-addled homebodies – still see value in trips to the public library?

A preference for print

We found that Gen Zers and millennials prefer books in print over e-books and audiobooks, even though their other favorite reading formats are decidedly digital, such as video game chats and web novels. American Gen Zers and millennials read an average of two print books per month – nearly double the average for e-books or audiobooks, according to our data.

The preference for print also manifests itself in the types of books Gen Z and millennials are borrowing and buying: 59% said they prefer the same story in graphical or manga format than in text only.

And while some graphic novels, comics and manga can be read on a screen, print is where these intricately illustrated books truly shine.

Beyond reading

We were most surprised by our finding that 23% of Gen Zers and millennials who don’t identify as readers nonetheless visited a physical library in the past 12 months.

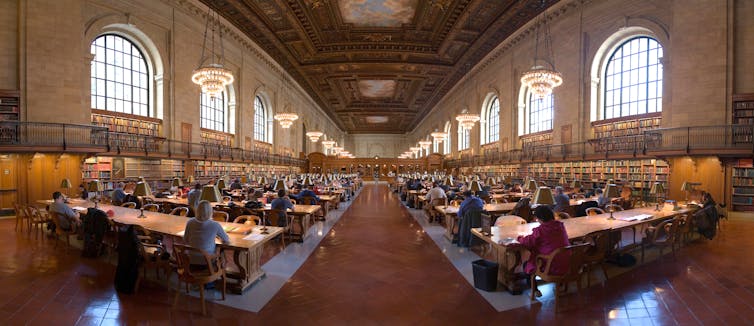

It’s a reminder that libraries don’t just serve as a repository for books. Patrons can record podcasts, make music, craft with friends or play video games. There are also quiet spaces with free Wi-Fi, perfect for students or people who work remotely.

Younger generations tend to be more values driven than older ones, and libraries’ ethos of sharing seems to resonate with Gen Zers and millennials – as does a space that’s free from the insipid creep of commercialism. At the library, there are no ads and no fees – well, provided you return your books on time – and no cookies tracking and selling your behavior.

U.S. census data also shows that younger generations are more racially diverse than older generations.

Our survey found that 64% of Black Gen Zers and millennials visited physical libraries in 2022, a rate that’s 10 percentage points higher than the general population. Meanwhile, Asian and Latino Gen Zers and millennials were more likely than the general population to say that browsing library shelves was a preferred way to discover new books.

A crucial moment for libraries

Though libraries have been forced to reckon with book bans and the politicization of public spaces, Gen Zers and millennials still see libraries as a kind of oasis – a place where doomscrolling and information overload can be quieted, if temporarily.

Perhaps Gen Zers’ and millennials’ library visits, like their embrace of flip phones and board games, are another life hack for slowing down.

Printed books won’t ping you or ghost you. And when young people eventually log back on to their devices, books make excellent props for #BookTok, the community on TikTok where readers review their favorite books.

Kathi Inman Berens, Associate Professor of Book Publishing and Digital Humanities, Portland State University and Rachel Noorda, Associate Professor of Publishing, Portland State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.