When businesspeople retire at an advanced age, it seldom makes headlines.

But when 92-year-old Rupert Murdoch announced in September that he was stepping away from his multicontinent media empire and turning it over to his son Lachlan, it was breaking news that generated countless stories speculating about the futures of two of his most storied holdings, Fox and News Corp.

As a scholar who studies media organizations and their political and economic influence, I see this level of attention as an indicator both of the significance of the companies Murdoch built and the way he used them to alter the media and political landscape.

Murdoch the believer … or opportunist?

Murdoch infused his print and television properties, first in his native Australia and later in the U.K. and the U.S., with a generally right-of-center slant.

But his reputation as a promoter of conservative ideals was at odds with his past. While a student at Oxford University, Murdoch kept a bust of Lenin in his room and annoyed his father, Sir Keith Murdoch, with his socialist views.

When his father died suddenly in 1952, Murdoch inherited a small newspaper in Adelaide and soon was using its profits to buy up suburban papers all over Australia, as well as licenses for television stations.

His conquest of the U.K. began in 1969 with the purchase of a majority interest in News of the World, a major circulation Sunday tabloid. Eventually, he would add to it the daily tabloid The Sun and the redoubtable but financially struggling Times and Sunday Times.

Through the 1970s, his politics moved to the right, culminating in his support – and The Sun’s much sought-after editorial endorsement – of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party.

Despite the conservative outlook of his publications, there always has been nagging speculation about the sincerity of Murdoch’s ideological beliefs – whether they were tightly held or simply manifestations of political opportunism and his ability to anticipate the popular mood. Murdoch’s The Sun backed the center-left Tony Blair when Conservative Party prime minister John Major fell out of favor in 1997.

His successes in the U.K. provided him with the strategic template for his eventual entry into the more lucrative U.S. market: Buy undervalued sources of content creation and then use their profits, along with a combination of emerging technology and political influence, to expand their distribution.

In the U.K., that meant the secretive construction of a high-tech automated printing facility that bypassed the labor unions. In the U.S., it might have contributed to a US$4.5 million book deal for House Speaker Newt Gingrich with Murdoch’s publishing house HarperCollins. It came as the media tycoon was facing questions about where the money for his U.S. television properties was coming from – questions, it was suggested by critics, that the speaker’s influence could help smooth over.

Building an American empire

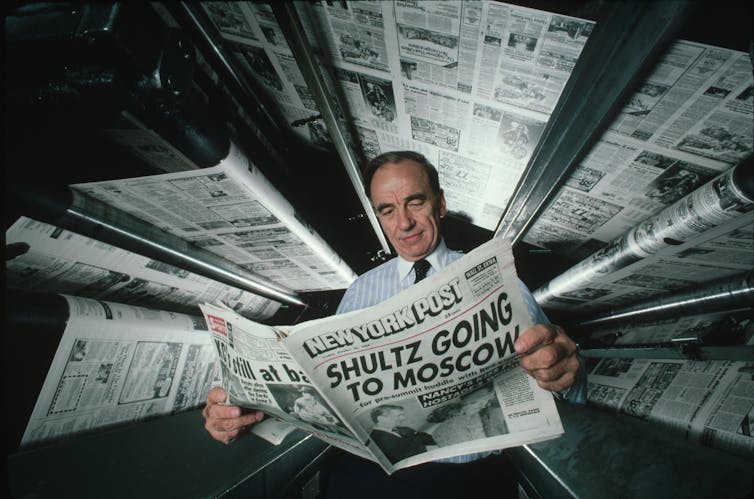

Murdoch’s American empire started in 1976 when he purchased the tabloid the New York Post. There, borrowing from his experience in the U.K., he flipped the newspaper’s ideology from liberal to conservative and used splash headlines and prurient content to more than double its circulation.

Also echoing a strategy he had employed in the U.K., he added the more respected Wall Street Journal to his holdings a number of years later, extending the reach of his influence from blue-collar to white-collar readers.

Anticipating the uncertain future of the newspaper business, Murdoch expanded his empire to include television.

He purchased the Twentieth Century Fox film and television studio in 1985 to provide both production facilities and a library of content. The following year, he bought the television station holdings of Metromedia to form the distribution nucleus of what would become the Fox television network.

Doing so required a series of moves to meet Federal Communications Commission regulations. First, Murdoch would have to become a U.S. citizen. Second, Fox would have to limit its hours of broadcast in order to avoid meeting the official definition of a network and in so doing break FCC rules that at the time stated that a single company could not be both a network and a syndicator of programs.

Third, he would have to sell the New York Post, since another rule prohibited common ownership of a daily newspaper and television station in the same city. The FCC would later allow him to repurchase the Post out of bankruptcy in 1993, rather than see the newspaper fold.

The birth of Fox News

Unable to secure licenses for terrestrial television stations in the U.K., Murdoch launched the Sky satellite service in 1989 as both a content provider and a distribution system. Among Sky’s channels was Sky News, the U.K.’s first 24-hour news channel. Once Sky News had become profitable, Murdoch announced he would bring his brand of 24-hour news to the U.S. By October 1996, Fox News Channel, led by former Republican Party strategist Roger Ailes, was on the air.

While Fox News is now very much associated with a viewership that skews older, conservative and white, the Fox broadcast network’s path to success with audiences and advertisers was initially based in its appeal to underserved audiences among young adults and African Americans.

Shows like “The Simpsons” and “Married … With Children” were seen as edgy in their representation of dysfunctional families. Meanwhile, “In Living Color,” “Roc,” “The Bernie Mac Show,” “Martin” and “Living Single” followed “The Cosby Show” playbook of focusing on Black authorship and autobiography to attract not just African Americans but audiences of all races and ethnicities.

When Fox secured rights to the National Football League’s NFC games in 1993, the network began targeting more mainstream audiences as well. As he had done in the newspaper business, Murdoch established his foothold in a niche market he perceived as being underserved and ripe for exploitation before setting his sights elsewhere.

A less-than-graceful exit

Despite his reputation as a buccaneer who took huge risks in expanding his holdings, skirting regulations and delaying repayments of loans from financial institutions, Murdoch avoided major legal and business setbacks for most of his career.

That only began to change in the mid-2000s.

First there was Myspace. News Corp. bought what was then among the world’s most popular websites in 2005. But it soon went into decline, weighed down by failures to update its technology and features. Then, in 2011, a backlash from a scandal involving the hacking of cellphone accounts of a murdered teenage girl, British service personnel killed in action and a host of celebrities forced the closure of Murdoch’s first U.K. newspaper, the News of the World.

More recently, News Corp. settled a lawsuit brought by the parents of the late Seth Rich, a Democratic National Committee staffer, after Fox News repeated right-wing conspiracy claims about the murdered man. It also reached a $787.5 million settlement with Dominion Voting Systems, which several Fox News hosts had accused of rigging the 2020 presidential election against Donald Trump. A similar defamation suit by Smartmatic is pending.

For a man whose career was built on a shrewdness for reading the media landscape, such failures might well leave a bitter taste in retirement. But nonetheless, Murdoch will step down from his empire leaving mighty footprints.

It remains to be seen how his son Lachlan will fill them – or if he also inherited his father’s instincts and will lay down tracks for the empire in a new and unexpected direction.

Bruce Drushel, Professor of Media, Journalism and Film, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.