When special counsel Jack Smith announced the charges he was bringing against former President Donald Trump for retaining government documents, he did something unusual: He invited the public to read the formal legal document, known as an indictment, detailing the allegations.

And many did – concluding not only that the indictment was well-written but engaging.

I study the ethics of using narrative and rhetoric in legal persuasion. I am also a lawyer. I know that nothing required Smith and his team at the Department of Justice to write this way. Although legal scholars have called for a more stringent standard, the law requires only that a federal indictment include a “plain, concise, and definite” outline of the “essential facts” of the case – just enough to help the defense attorney understand what the client faces. Prosecutors could have cleared this hurdle by writing a technocratic document intelligible only to other criminal law insiders.

Instead, they wrote what in legal circles is called a “speaking” indictment. This indictment told a story. And not just any story – one laced with rhetorical and narrative techniques to not just help the public understand the case, but more, to persuade readers that the prosecution is justified.

Show, don’t tell

Here are some examples of how the indictment tells a story aimed at persuading readers:

The storage boxes: Trump’s now famous boxes are introduced by, first, the use of selective detail to paint a sentimental scrapbooking scene: We imagine Trump gathering what are described as “newspapers, press clippings, letters, notes, cards, photographs, official documents, and other materials in cardboard boxes.” Yet among this image of keepsakes, notes the next paragraph, were documents about “defense and weapons capabilities of both the United States and foreign countries; United States nuclear programs; [and] potential vulnerabilities of the United States and its allies to military attack.”

Mar-a-Lago: These boxes didn’t remain at the White House; after Trump’s presidency ended, he took them to Mar-a-Lago. Prosecutors could have just referred to Trump’s “Florida residence” or listed a street address. But doing so might not only be boring but also leave readers with their own stock sense of what a “residence” is.

So they brought Mar-a-Lago to life, describing it as an “active social club” with “more than 25 guest rooms, two ballrooms, a spa, [and] a gift store” that, in the relevant period, hosted “150 social events, including weddings, movie premieres, and fundraisers that together drew tens of thousands of guests.” It was into this Gatsbyesque scene that Trump brought his boxes.

True, Mar-a-Lago does have a “storage room” where many boxes were put. But here, too, indictment authors counter readers’ image of what that might mean. This isn’t a room in a quiet basement corner, but rather one in a hallway with “multiple outside entrances,” near high-traffic areas like a “liquor supply closet” and “linen room.” In a moment of almost Shakespearean comedy, the indictment shows Trump employees in this setting chancing upon confidential documents spilled out on the floor. One texts, “I opened the door and found this…” to which the other replies, “Oh no oh no.”

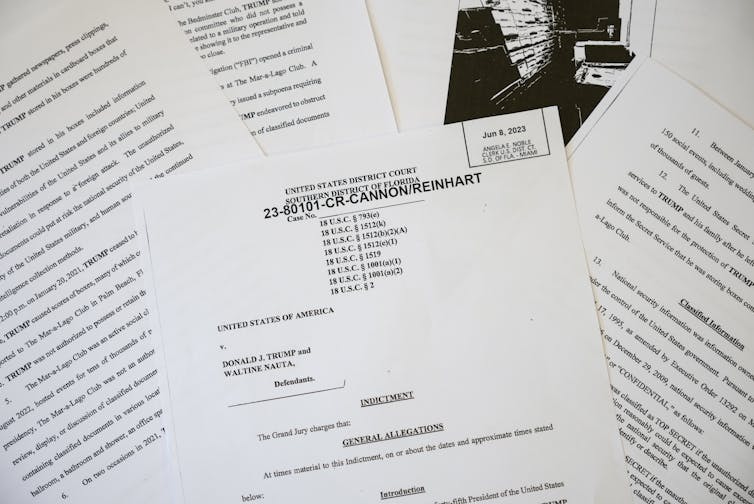

The photos: Readers are not merely told that Trump stored highly sensitive intelligence materials at less-than-secure locations throughout Mar-a-Lago, they are shown photos of boxes on a stage and in a bathroom.

These images not only keep readers engaged by breaking up the text but also reinforce the Department of Justice’s written allegations. And because viewers assume images to be true without reflection, including this photographic evidence as visual allegations is especially effective.

Plot inferences: As with any nonfiction story, the indictment has gaps. Readers know that phone calls occurred but not what was said. Readers know that actions took place one after another but not that the first caused the second. But through careful arrangement, the authors prime readers to fill in these gaps.

Using Trump’s own words, the indictment encourages readers to imagine him, to hear him, thinking out loud: “I don’t want anybody looking through my boxes … wouldn’t it be better if we just told them we don’t have anything here? … isn’t it better if there are no documents?” Then, starting a page later, readers twice see Trump speak to an employee for less than half a minute. They don’t know what’s said, but in both cases the next sentence after each phone call shows that employee moving boxes in, and then out, of the storage room.

Readers could infer what’s going on: Trump ordered that the boxes be moved and did so to conceal their contents. Without even realizing it, readers complete the story, giving content to the phone calls and meaning to the actions that followed them.

Throughout the indictment, writing techniques such as these transport readers through a story portal so that they see Mar-a-Lago, hear Trump barking orders and feel his motivations; the case’s disparate facts cohere into a vivid, engaging story.

‘It’s only one side’

A bare-bones, legalistic indictment would do none of these things. Nonexpert readers would gloss over it. The public would be left with just Trump’s claims about what the case was about. In contrast, Smith’s approach helps the public understand this historic prosecution.

So maybe more prosecutors should write this way.

But not every defendant has Trump’s power or influence. Not every defendant can broadcast a story for an indictment to then counter. Instead, an indictment full of persuasive storytelling techniques might frame the public’s first, and sometimes only, impressions.

Unlike in a Supreme Court case, where both sides get to share their story of what happened and should happen next, at the indictment stage the prosecutor is the only one speaking. If such a case settles before trial through a plea agreement, or if after trial the case isn’t appealed, then the defendant may never have a chance to present a public, written story.

Prosecutors wield incredible power. This includes the power to persuade through storytelling. While admiring the writing of Smith and his team here, readers should also be aware: It’s only one side of the story.

Derek H. Kiernan-Johnson, Teaching Professor of Law, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.