Bitcoin boosters like to claim Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies, are becoming mainstream. There’s a good reason to want people to believe this.

The only way the average punter will profit from crypto is to sell it for more than they bought it. So it’s important to talk up the prospects to build a “fear of missing out”.

There are loose claims that a large proportion of the population – generally in the range of 10% to 20% – now hold crypto. Sometimes these numbers are based on counting crypto wallets, or on surveying wealthy people.

But the hard data on Bitcoin use shows it is rarely bought for the purpose it ostensibly exists: to buy things.

Little use for payments

The whole point of Bitcoin, as its creator “Satoshi Nakamoto” stated in the opening sentence of the 2008 white paper outlining the concept, was that:

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.

The latest data demolishing this idea comes from Australia’s central bank.

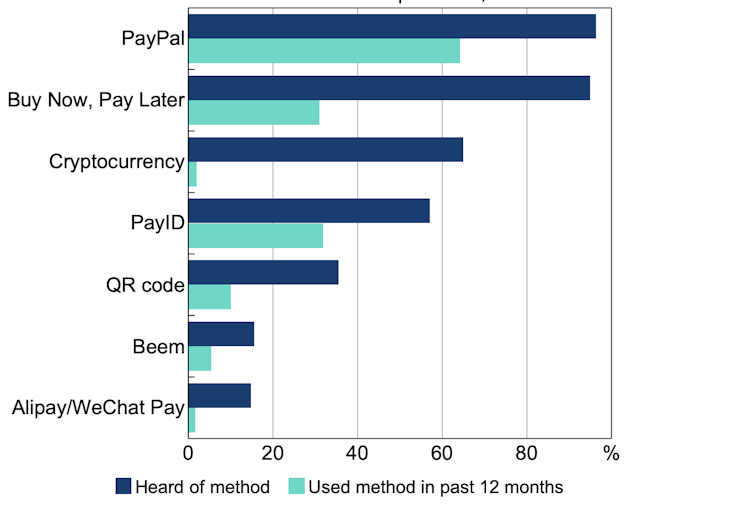

Every three years the Reserve Bank of Australia surveys a representative sample of 1,000 adults about how they pay for things. As the following graph shows, cryptocurrency is making almost no impression as a payments instrument, being used by no more than 2% of adults.

Payment methods being used by Australians

By contrast more recent innovations, such as “buy now, pay later” services and PayID, are being used by around a third of consumers.

These findings confirm 2022 data from the US Federal Reserve, showing just 2% of the adult US population made a payment using a cryptocurrrency, and Sweden’s Riksbank, showing less than 1% of Swedes made payments using crypto.

The problem of price volatility

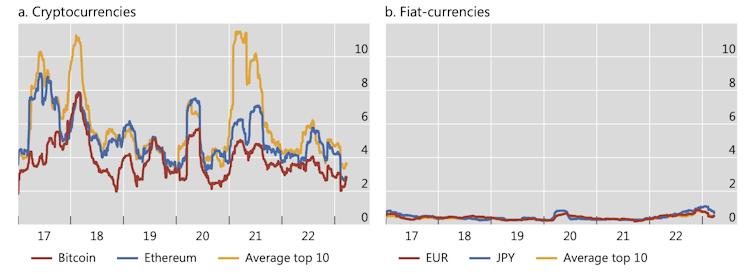

One reason for this, and why prices for goods and services are virtually never expressed in crypto, is that most fluctuate wildly in value. A shop or cafe with price labels or a blackboard list of their prices set in Bitcoin could be having to change them every hour.

The following graph from the Bank of International Settlements shows changes in the exchange rate of ten major cryptocurrencies against the US dollar, compared with the Euro and Japan’s Yen, over the past five years. Such volatility negates cryptocurrency’s value as a currency.

Cryptocurrency’s volatile ways

There have been attempts to solve this problem with so-called “stablecoins”. These promise to maintain steady value (usually against the US dollar).

But the spectacular collapse of one of these ventures, Terra, once one of the largest cryptocurrencies, showed the vulnerability of their mechanisms. Even a company with the enormous resources of Facebook owner Meta has given up on its stablecoin venture, Libra/Diem.

This helps explain the failed experiments with making Bitcoin legal tender in the two countries that have tried it: El Salvador and the Central African Republic. The Central African Republic has already revoked Bitcoin’s status. In El Salvador only a fifth of firms accept Bitcoin, despite the law saying they must, and only 5% of sales are paid in it.

Storing value, hedging against inflation

If Bitcoin’s isn’t used for payments, what use does it have?

The major attraction – one endorsed by mainstream financial publications – is as a store of value, particularly in times of inflation, because Bitcoin has a hard cap on the number of coins that will ever be “mined”.

As Forbes writers argued a few weeks ago:

In terms of quantity, there are only 21 million Bitcoins released as specified by the ASCII computer file. Therefore, because of an increase in demand, the value will rise which might keep up with the market and prevent inflation in the long run.

The only problem with this argument is recent history. Over the course of 2022 the purchasing power of major currencies (US, the euro and the pound) dropped by about 7-10%. The purchasing power of a Bitcoin dropped by about 65%.

Speculation or gambling?

Bitcoin’s price has always been volatile, and always will be. If its price were to stabilise somehow, those holding it as a speculative punt would soon sell it, which would drive down the price.

But most people buying Bitcoin essentially as a speculative token, hoping its price will go up, are likely to be disappointed. A BIS study has found the majority of Bitcoin buyers globally between August 2015 and December 2022 have made losses.

The “market value” of all cryptocurrencies peaked at US$3 trillion in November 2021. It is now about US$1 trillion.

Bitcoins’s highest price in 2021 was about US$60,000; in 2022 US$40,000 and so far in 2023 only US$30,000. Google searches show that public interest in Bitcoin also peaked in 2021. In the US, the proportion of adults with internet access holding cryptocurrencies fell from 11% in 2021 to 8% in 2022.

UK government research published in 2022 found that 52% of British crypto holders owned it as a “fun investment”, which sounds like a euphemism for gambling. Another 8% explicitly said it was for gambling.

The UK parliament’s Treasury Committee, a group of MPs who examine economics and financial issues, has strongly recommended regulating cryptocurrency as form of gambling rather than as a financial product. They argue that continuing to treat “unbacked crypto assets as a financial service will create a ‘halo’ effect that leads consumers to believe that this activity is safer than it is, or protected when it is not”.

Whatever the merits of this proposal, the UK committtee’s underlying point is solid. Buying crypto does have more in common with gambling than investing. Proceed at your own risk, and and don’t “invest” what you can’t afford to lose.

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.