Takeaways:

A new federal agency to regulate AI sounds helpful but could become unduly influenced by the tech industry. Instead, Congress can legislate accountability.

Instead of licensing companies to release advanced AI technologies, the government could license auditors and push for companies to set up institutional review boards.

The government hasn’t had great success in curbing technology monopolies, but disclosure requirements and data privacy laws could help check corporate power.

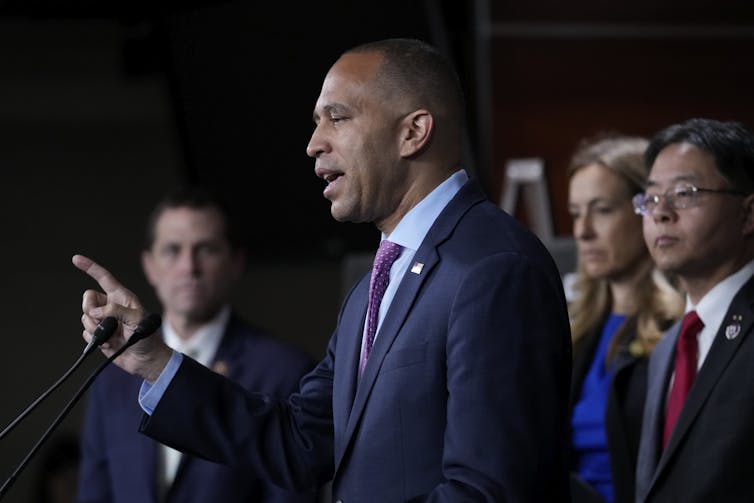

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman urged lawmakers to consider regulating AI during his Senate testimony on May 16, 2023. That recommendation raises the question of what comes next for Congress. The solutions Altman proposed – creating an AI regulatory agency and requiring licensing for companies – are interesting. But what the other experts on the same panel suggested is at least as important: requiring transparency on training data and establishing clear frameworks for AI-related risks.

Another point left unsaid was that, given the economics of building large-scale AI models, the industry may be witnessing the emergence of a new type of tech monopoly.

As a researcher who studies social media and artificial intelligence, I believe that Altman’s suggestions have highlighted important issues but don’t provide answers in and of themselves. Regulation would be helpful, but in what form? Licensing also makes sense, but for whom? And any effort to regulate the AI industry will need to account for the companies’ economic power and political sway.

An agency to regulate AI?

Lawmakers and policymakers across the world have already begun to address some of the issues raised in Altman’s testimony. The European Union’s AI Act is based on a risk model that assigns AI applications to three categories of risk: unacceptable, high risk, and low or minimal risk. This categorization recognizes that tools for social scoring by governments and automated tools for hiring pose different risks than those from the use of AI in spam filters, for example.

The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology likewise has an AI risk management framework that was created with extensive input from multiple stakeholders, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Federation of American Scientists, as well as other business and professional associations, technology companies and think tanks.

Federal agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Federal Trade Commission have already issued guidelines on some of the risks inherent in AI. The Consumer Product Safety Commission and other agencies have a role to play as well.

Rather than create a new agency that runs the risk of becoming compromised by the technology industry it’s meant to regulate, Congress can support private and public adoption of the NIST risk management framework and pass bills such as the Algorithmic Accountability Act. That would have the effect of imposing accountability, much as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and other regulations transformed reporting requirements for companies. Congress can also adopt comprehensive laws around data privacy.

Regulating AI should involve collaboration among academia, industry, policy experts and international agencies. Experts have likened this approach to international organizations such as the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The internet has been managed by nongovernmental bodies involving nonprofits, civil society, industry and policymakers, such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and the World Telecommunication Standardization Assembly. Those examples provide models for industry and policymakers today.

Licensing auditors, not companies

Though OpenAI’s Altman suggested that companies could be licensed to release artificial intelligence technologies to the public, he clarified that he was referring to artificial general intelligence, meaning potential future AI systems with humanlike intelligence that could pose a threat to humanity. That would be akin to companies being licensed to handle other potentially dangerous technologies, like nuclear power. But licensing could have a role to play well before such a futuristic scenario comes to pass.

Algorithmic auditing would require credentialing, standards of practice and extensive training. Requiring accountability is not just a matter of licensing individuals but also requires companywide standards and practices.

Experts on AI fairness contend that issues of bias and fairness in AI cannot be addressed by technical methods alone but require more comprehensive risk mitigation practices such as adopting institutional review boards for AI. Institutional review boards in the medical field help uphold individual rights, for example.

Academic bodies and professional societies have likewise adopted standards for responsible use of AI, whether it is authorship standards for AI-generated text or standards for patient-mediated data sharing in medicine.

Strengthening existing statutes on consumer safety, privacy and protection while introducing norms of algorithmic accountability would help demystify complex AI systems. It’s also important to recognize that greater data accountability and transparency may impose new restrictions on organizations.

Scholars of data privacy and AI ethics have called for “technological due process” and frameworks to recognize harms of predictive processes. The widespread use of AI-enabled decision-making in such fields as employment, insurance and health care calls for licensing and audit requirements to ensure procedural fairness and privacy safeguards.

Requiring such accountability provisions, though, demands a robust debate among AI developers, policymakers and those who are affected by broad deployment of AI. In the absence of strong algorithmic accountability practices, the danger is narrow audits that promote the appearance of compliance.

AI monopolies?

What was also missing in Altman’s testimony is the extent of investment required to train large-scale AI models, whether it is GPT-4, which is one of the foundations of ChatGPT, or text-to-image generator Stable Diffusion. Only a handful of companies, such as Google, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft, are responsible for developing the world’s largest language models.

Given the lack of transparency in the training data used by these companies, AI ethics experts Timnit Gebru, Emily Bender and others have warned that large-scale adoption of such technologies without corresponding oversight risks amplifying machine bias at a societal scale.

It is also important to acknowledge that the training data for tools such as ChatGPT includes the intellectual labor of a host of people such as Wikipedia contributors, bloggers and authors of digitized books. The economic benefits from these tools, however, accrue only to the technology corporations.

Proving technology firms’ monopoly power can be difficult, as the Department of Justice’s antitrust case against Microsoft demonstrated. I believe that the most feasible regulatory options for Congress to address potential algorithmic harms from AI may be to strengthen disclosure requirements for AI firms and users of AI alike, to urge comprehensive adoption of AI risk assessment frameworks, and to require processes that safeguard individual data rights and privacy.

Learn what you need to know about artificial intelligence by signing up for our newsletter series of four emails delivered over the course of a week. You can read all our stories on generative AI at TheConversation.com.

Anjana Susarla, Professor of Information Systems, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Puzzles: Solving puzzles supports the development of skills such as concentration, self-regulation, critical thinking and spatial recognition.

Puzzles: Solving puzzles supports the development of skills such as concentration, self-regulation, critical thinking and spatial recognition.

Epsom Salt – Named for a bitter saline spring at Epsom in Surrey, England, Epsom salt is not actually salt but a naturally occurring mineral compound of magnesium sulfate. Long known as a natural remedy for several ailments, Epsom salt can be used to relax muscles and relieve pain in the shoulders, neck and back. It can also be applied to sunburns or dissolved in the bath to help relieve sore muscles or detox.

Epsom Salt – Named for a bitter saline spring at Epsom in Surrey, England, Epsom salt is not actually salt but a naturally occurring mineral compound of magnesium sulfate. Long known as a natural remedy for several ailments, Epsom salt can be used to relax muscles and relieve pain in the shoulders, neck and back. It can also be applied to sunburns or dissolved in the bath to help relieve sore muscles or detox.